What can a dyadic perceptual task tell us about cognition in real life?

- 4 minsPerception is simply experiecing the world through our senses. Everyday we process sensory information to guide useful behavior, like searching for your car keys in a pile of keys. Or, if you have experiences playing badminton, which is a super fast-paced sport, you’d frequently run into instances where you have to determine wehther the shuttle lands inside, outside, or on the court line. This is an example of a process called perceptual decision-making because you make decisions based on what you see using your visual senses. As such it is a central aspect, or even some call it a “window” to understanding our cognition.

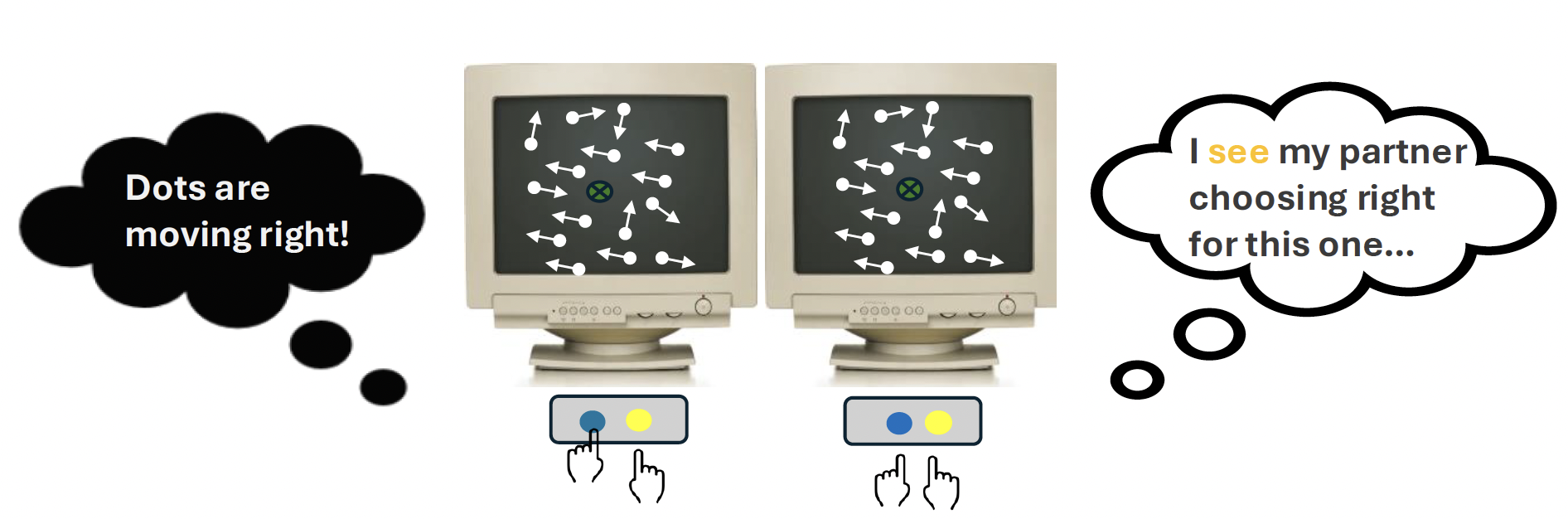

In the research world of visual decision-making, it’s been known that people are biased by their previous choices when they make decisions. Simple behavioral experiments demonstrated this. These experiments, often long and boring, invovled people sitting in front of a computer screen and repeatedly make a decision in response to the stimulus they see. For example, a visual simulus can be a cloud of dots either dominantly moving towards the right or left. Every time when the stimulus appears, people have to make a speeded response on whether it’s moving rightward or leftward.

In many of these cases, it’s been shown that what people chose previously, those decisions accumulated into a bias when they make the next decision even when the successive stiumulus are uncorrelated. That is, if you decided that those dots were moving rightward, then there’s a higher likelihood that you would choose rightward again. It is facinating and reveals a lot about how we huamn beings navigate the uncertain world. One can dive as deep into the research rabbit hole as they wish to understand this.

But these studies have traditionally focused on one person only. By doing this, one is assuming that humans are isolated “heads” out and about experiencing the world. The physical world we experience everyday is not just us mentally processing a specific sensory information, rather it is full of interactions with our surrounding environment. For instance, when searching for your key, you might have remembered discussing with your mom where it was last found. Or, you might have searched together with your mom, while observing where she’s looking of or even facial expressions to gain insights about the whereabouts of the key. What we experience everyday does not only entail processing these sensory information but also interactions with other people.

A two-person appraoch

I included social interaction in this classical perceptual experiment to better understand perception and behavior. In other words, I extended this individual setup to a dyadic one, to see how, given what we already know about choice history bias, whether observing your dyadic partner chooses would in turn influence what you choose and vice versa.

This experimental methodology we designed in the research domain of choice history and decision-making is new, however the concept is not so new. The idea goes back to what’s called the embodied cognition, which suggests that how we think and behave are shaped by bodily interactions. For example, when you look at where your friend is looking at, you might develop some understanding about what your friend intends to do. Or you smile back when a stranger smiles at you.

Our behavior emerges from our real-time interactions with the surrounding environment. It’s kind of radical to think about our brain and cognition in this way, because it has not always been that way. Rather it’s this idea that our brain generates behaviors, or our brain is separated from our body, that has traditionally dominated the thinking.

People do not ignore each other’s actions

I carried out a joint perceptual task and collected behavioral data from people grouped in dyads. Our results indicated that people do not ignore other’s choices when they make decisions.

Some impact I see this study brings to the academic community are:

-

The joint design allows for a systematic comparison with the findings on choice history bias from those of the single-participant designs. Moreover, this method is generalizable across various contexts and populations e.g, Human-AI interaction. Since humans treat computers as social actors, what if, say, a virtual assistant consistently reports to you the wrong information, does that change the way you trust or interact with it?

-

First to document social interaction influencing choice history bias effect. The implications extend to other scenarios. For example, I wonder how often this choice bias effect is seen in political groups where it invovles collective thinking.

-

Publication in Nature Scientific Reports.

Lessons and takeaways

-

Multiple iterations is always needed until the task is fully functional and replicable- being able to handle deep frustrations is part of the process.

-

The practice of synthetic data simulation is always, not only a great sanity check on data integrity, but also a excellent tool to build a solid understanding of the analysis process.