Mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive

- 5 minsMutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive or MECE, is a framewok that is commonly used for solving ambiguous questions, such as how many people in in the Netherlands apply to data science jobs each year? Should I open a cafe in Leiden?

This framework is a structured approach to solve vague business problem by breaking the problem down to definable bits and pieces. In consulting, when people appraoch these types of probelems, they start with an anchor number like population of the city, then segment that population group by sex, age, etc. Then they work their way down the defined items using a combination of logic and quantitative thinking to come up with a concrete solution to the question.

MECE is a good framework, because each items in the framework does not overlap; moreover, they are exahustive, indicating all the universe of possibilities that pertain to the problem. The profitability framework is an example that demonstrates MECE.

This framework is also useful in scientific research. For example, let’s say we wanted to know how huamns make perceptual choices when they know their actions are being observed. To solve this problem, I would first read a lot of the litertaure to gain subject matter expertise. Following this, I would define the research questions and formulate testable hypotheses in both natural language texts and quantitative parameters. For the latter, applying the MECE framework is useful. The research objective was to determine whether perceptual decision-making is more of an individualistic (independent of the co-actor’s action) or collective (contingent on the co-actor’s action) process despite the co-actor’s actions being irrelevant to the present decision.

We come up with competing hypotheses in natural English language:

- Hypothesis a: The participants equally weigh their own and their partner’s decision history

- Hypothesis b: The participants alternate from their partner’s decisions

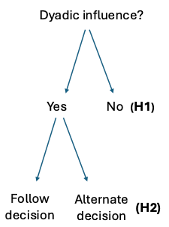

Here is a diagram describing how the formulated hypotheses.

Nevertheless, this is confusing. Normally in hypothesis testing, one is called a null (no effect) and the other is the alternative (effect). Hypothesis b is not really the alternative to hypothesis a. Rather it presents as one of the options to an alternative statement compared to Hypothesis a.

Often the process of formulating hypotheses require multiple iterations to get them unambiguous and quantitatively accurate.Here, the statements need to be revised for clarity. If we revise the statements as:

- Hypothesis a1: The participants equally weigh their own and their partner’s decision history

- Hypothesis b1: The participants unequally weigh their own and their partner’s decision history

This is conceptually redundant and will not work. The reason is the word unequally is the catch-all composite that lumps together several distinct possibilities.

To make the hypotheses mutually exclusive and statistically testable, we need statements that are orthogonal or in stark contrast such that there are no overlapping possibilities in between.

Therefore, we revise the statements as following:

- Hypothesis 1. The participants equally weigh their own and their partner’s decision history

- Hypothesis 2. The participants do not weigh equally their own and their partner’s decision history.

Now we have a clear null and alternative rather than null and something else.

The first hypothesis suggests that the choice history bias effect is not limited to a specific actor in the dyad but relates to the combined sequence of decisions by the dyad. Alternatively, hypothesis 2 assumes the choice history effect is influenced by the specific actor.

Here, we will see how the contrasting statements are cleanly expressed in quantitative terms. Since we use a stewpise generalized linear modeling approach (GLM) to test the extent to which the hypotheses are supported, we express the statements in terms of the model’s coefficient estimates. In the GLM, the participant’s choice responses is the dependent variable that is coded as 0 (left) or 1 (right). The predictors are effect-coded (+1 for right, -1 for left; +1 for own, -1 for partner). The corresponding regression coefficient β captures the influence of self versus partner decisions.

If H1 is supported, we examine how the choice history effect depends on the specific actor. In particular, the participants could either follow or deviate from their partner’s decision. To follow the decision means if the dyadic partner responded left, the participant is likely to choose left, and vice versa for right response (i.e., a “choice repetition”, regression coefficient estimate β > 0). To deviate from the decision means if the dyadic partner responded left, the participant is likely to respond oppositely from this by choosing right, vice versa for right response (i.e., a “choice alternation”, regression coefficient estimate β < 0).

Consider if we have adopted Hypothesis a1 and b1. Hypothesis b1 will be problematic because the term “unequally” is too broad. It conflates multiple possibilities into one category. In other words, the word “unequally” could describe multiple, qualitatively distinct outcomes: participants might follow their partner’s choices (β > 0), alternate from them (β < 0), or show no contingent effect at all (β ≈ 0). The last case is fundamentally different from “equal” weighting, yet it would still technically fall under the umbrella of “unequal.” Together, Hypothesis b1 is not mutually exclusive with Hypothesis a1, thus it is not operationally MECE, making interpretation of the estimated coefficients ambiguous.

Coming to the statistical modeling, the appraoch is also MECE. The first step in the stepwise modeling is to create a model that covers all the “universe of possibilities” that influence the decision. For example, it could be the previous actor or the response up to two trials back, it could also be the order in which the actor responded, etc. We need such a big and relatively sophisticated model that test the hypotheses in a way of steps and simplifications until we arrive at a conclusion. For more, check out this paper.